Introduction

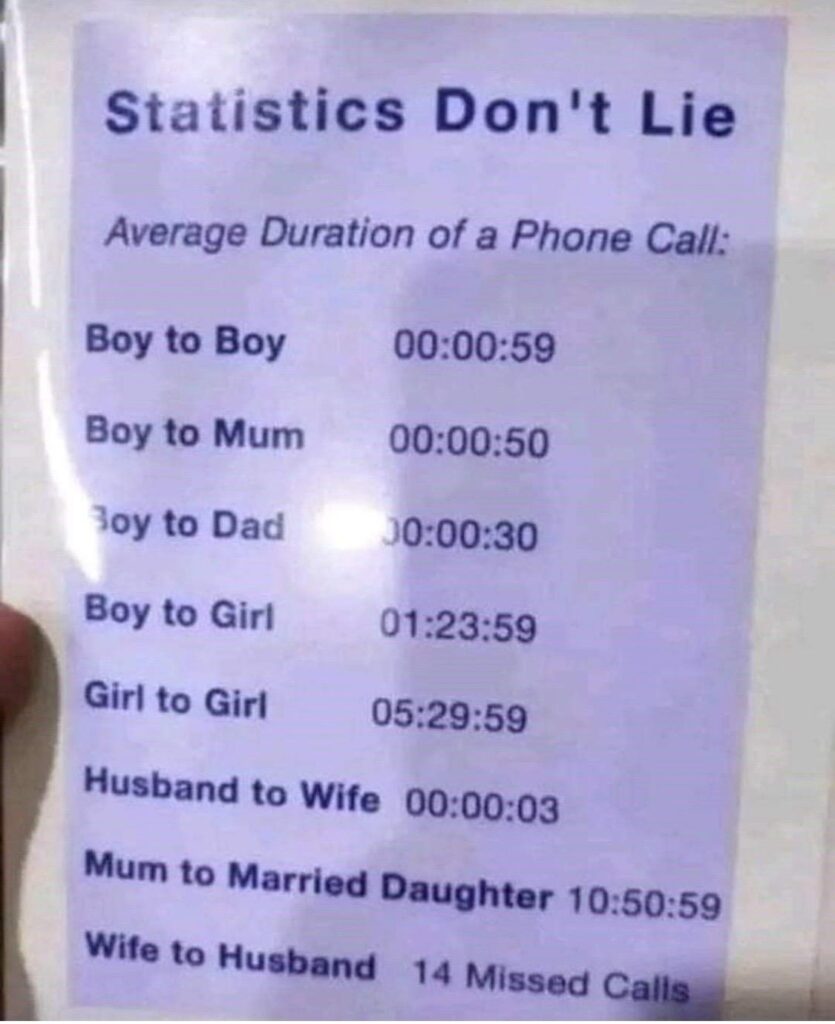

The viral image showing different phone call durations between sexes—“Boy to Boy: 59 seconds, Girl to Girl: 5 hours”—is intended as humour. But behind the joke lies a body of scientific research on gender, communication, and relational maintenance. Studies in psychology, linguistics, and communication science reveal that men and women often use phone conversations differently, shaped by social roles, intimacy needs, and emotional expression styles.

This article reviews the science of phone durations between sexes, why these patterns exist, and what they reveal about mental health, relationships, and wellbeing.

1. Gendered communication styles

Research consistently shows that women tend to prioritise expressive communication, whereas men are more likely to engage in instrumental communication (Tannen, 1990; Leaper & Ayres, 2007).

- Women: Use conversations to build connection, express emotions, and maintain closeness. This often translates into longer call durations.

- Men: More likely to exchange information, solve a problem, or complete a task, resulting in shorter calls.

Example: In a study of adolescent friendships, girls reported more frequent and longer phone calls, while boys preferred face-to-face group activities (Raffaelli & Duckett, 1989).

2. Phone calls as relational maintenance

Phone communication is not just about information—it’s also about maintaining relationships.

- Romantic partners: Research shows that women initiate more maintenance behaviours (e.g., reassurance, talk about feelings), which can prolong calls (Canary & Stafford, 1992).

- Friendships: Same-sex female friendships typically feature longer and more self-disclosing conversations, both face-to-face and by phone (Caldwell & Peplau, 1982).

This supports the stereotype in the image: “Girl to Girl” calls being longest.

3. The psychology of “short male calls”

The image jokes that “Boy to Dad” lasts 30 seconds and “Husband to Wife” just 3 seconds. This exaggeration aligns with research showing that men communicate differently with family versus peers.

- Studies suggest men often have briefer and less emotionally expressive conversations with parents, especially fathers (Noller & Bagi, 1985).

- Husbands in some studies reported shorter calls and less emotional talk with wives compared to wives calling husbands (Acitelli, 1992).

However, it is not simply disinterest—it often reflects a preference for efficiency and avoidance of emotional over-disclosure.

4. Technology and gendered communication

Modern research also shows how smartphones and messaging apps have shifted patterns:

- Women are more likely to use voice calls, messaging, and social media to maintain closeness across distance (Thompson & Cupples, 2008).

- Men lean more towards utilitarian contact (e.g., arranging meetings, confirming details).

This continues to explain why average call length differs by sex, but total communication time (including texting) may balance out more.

5. Implications for mental health

a) Social support and wellbeing

Longer calls are often linked to greater perceived emotional support, especially for women (Taylor et al., 2000). Emotional disclosure predicts lower stress and better coping outcomes.

b) Loneliness and isolation

Short, functional conversations—common in male communication—may limit opportunities for emotional support, contributing to loneliness if not balanced with deeper interaction.

c) Relationship satisfaction

Couples who balance communication preferences—short updates for efficiency, longer calls for emotional connection—tend to report greater satisfaction (Stafford & Canary, 1991).

Checklist of key findings

- Women’s phone calls are longer and more emotionally expressive.

- Men’s calls are shorter and task-oriented.

- Friendship calls (especially female-to-female) are longest.

- Romantic calls vary, with women generally initiating longer maintenance calls.

- Emotional support through phone calls is linked to better mental health outcomes.

- Couples can increase satisfaction by aligning communication styles.

References

- Acitelli, L.K. (1992) ‘Gender differences in relationship awareness and communication in marriage’, Family Relations, 41(1), pp. 63–67.

- Barclay, P. (2010) ‘Altruism as a courtship display: Some effects of third-party generosity on audience perceptions’, British Journal of Psychology, 101(1), pp.123–135.

- Caldwell, M.A. & Peplau, L.A. (1982) ‘Sex differences in same-sex friendship’, Sex Roles, 8(7), pp. 721–732.

- Canary, D.J. & Stafford, L. (1992) ‘Relational maintenance strategies and equity in marriage’, Communication Monographs, 59(3), pp. 243–267.

- Fiske, S.T. et al. (2007) ‘Universal dimensions of social cognition: Warmth and competence’, Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(2), pp. 77–83.

- Leaper, C. & Ayres, M.M. (2007) ‘A meta-analytic review of gender variations in adults’ language use’, Psychological Bulletin, 133(6), pp. 923–947.

- Noller, P. & Bagi, S. (1985) ‘Parent-adolescent communication’, Journal of Adolescence, 8(2), pp. 125–144.

- Nye, C.D. et al. (2012) ‘Vocational interests and performance: A meta-analysis of person–environment fit’, Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(3), pp. 553–567.

- Raffaelli, M. & Duckett, E. (1989) ‘“We were just talking …”: Conversations in early adolescent friendships’, Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 18(6), pp. 567–582.

- Savickas, M.L. & Porfeli, E.J. (2012) ‘Career Adapt-Abilities Scale (CAAS): Construction, reliability and measurement equivalence’, Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(3), pp. 661–673.

- Stafford, L. & Canary, D.J. (1991) ‘Maintenance strategies and romantic relationship type, gender and relational characteristics’, Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 8(2), pp. 217–242.

- Taylor, S.E. et al. (2000) ‘Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: Tend-and-befriend, not fight-or-flight’, Psychological Review, 107(3), pp. 411–429.

- Tannen, D. (1990) You Just Don’t Understand: Women and Men in Conversation. New York: Ballantine.

- Thompson, L. & Cupples, J. (2008) ‘Seen and not heard? Text messaging and digital sociality’, Social & Cultural Geography, 9(1), pp. 95–108.